Risk attitude is the amount of risk an organisation is willing to accept to achieve its objectives. In a time of unprecedented aid worker casualties, Alan Mordaunt explains why having a risk attitude statement is so important for NGOs.

Today’s context of heightened risk

Earlier this year, GISF published its State of Practice report, reflecting on the changes that have occurred in humanitarian security risk management over recent years and decades. This was followed by a blog written by Abby Stoddard, Director of Humanitarian Outcomes and lead author of the State of Practice.

The opening of Abby’s blog stands out for its clear articulation of today’s alarming reality. “Humanitarian aid workers are more likely to die from violence than any other job-related cause,” Abby writes. “Last year was especially brutal, with upwards of 260 aid workers killed – more than double the average of the prior three years.”

This troubling statistic suggests that as insecurity and conflict become more prevalent, we may not always be able to improve or maintain the safety of our staff. The spectrum of threats may continue in the wrong direction, and losing sight of what’s essential is easy. This is why it’s now more important than ever for organisations to clearly define the levels of risk they can accept.

Understanding Risk Attitude: terminology and purpose

A risk attitude statement outlines the amount of risk an organisation is willing to accept to achieve its objectives. It is a simple but critical link between a Board of Directors, Executive Leadership and Risk Managers. A risk attitude statement supports operationally focused teams making informed decisions that balance their needs to push boundaries with an agreed limit or red line. By clearly defining the levels of risk an organisation is willing to accept, a risk attitude supports more consistent and transparent decision-making. It ultimately contributes to the effectiveness and safety of humanitarian operations.

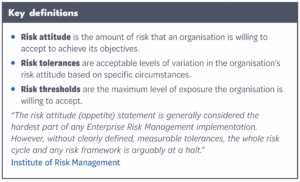

An organisational risk attitude can be described in various ways. Terms such as risk appetite, preference, or capacity are often used interchangeably, depending on the context and the organisation. Despite the different terminologies, the core purpose remains: to align risk indicators across various operational areas, ensuring that an organisation works within its agreed parameters.

A well-defined risk attitude is not just a theoretical concept. It is a practical tool that helps organisations monitor and assess whether they are taking on too much or too little risk relative to their capacity and strategic objectives. When done correctly, it should provide a framework for consistently evaluating risks across the organisation. This makes it a vital tool for strategic planning and day-to-day operations.

Bridging the gap between international and local organisations

International organisations often have the advantage of more resources. They may also have more advanced security risk management (SRM) structures, and greater experience. This can enable them to navigate complex security environments better.

On the other hand, local partners frequently face significant challenges due to limited resources. This makes them more vulnerable to insecurity and this disparity can sometimes lead to an unfair distribution of risks.

GISF has published a guide on Partnerships and Security Risk Management. This document suggests that challenges can be effectively managed by establishing a clear and well-documented risk attitude within a partnership. Joint SRM reviews and the development of shared security policies can help both parties set clear roles, responsibilities, and expectations. This collaboration promotes mutual respect and balanced risk-sharing. Ultimately, it strengthens the security and sustainability of humanitarian operations.

Integrating risk attitude into organisational culture

Effectively integrating a well-defined risk attitude statement into the wider organisational culture is another good way to encourage sustainable security practices aligned with operational goals. According to ISO 31000:2018 guidelines, risk management, including the articulation of risk attitude, should not be treated as a separate function. It should be an integral part of all organisational activities. That includes governance, leadership, and decision-making. This integration ensures that the organisation’s risk attitude informs and guides behaviours, decision-making, and interactions at every level.

The recent GISF guide on Security Risk Management (SRM) Strategy and Policy Development stresses the need to embed a risk attitude deeply into an organisation’s culture. It suggests integrating the risk attitude across all strategic areas, promoting collaboration between different departments, and clearly defining roles and responsibilities. This ensures that the risk attitude becomes a fundamental part of the organisation’s operations, strengthening resilience and supporting business continuity. The guide also highlights the importance of effectively communicating the risk attitude, so it is consistently understood and applied throughout the organisation, ultimately contributing to long-term safety and adaptability. This guidance is invaluable for developing a robust and organisation-wide risk management culture.

The recent GISF guide on Security Risk Management (SRM) Strategy and Policy Development stresses the need to embed a risk attitude deeply into an organisation’s culture. It suggests integrating the risk attitude across all strategic areas, promoting collaboration between different departments, and clearly defining roles and responsibilities. This ensures that the risk attitude becomes a fundamental part of the organisation’s operations, strengthening resilience and supporting business continuity. The guide also highlights the importance of effectively communicating the risk attitude, so it is consistently understood and applied throughout the organisation, ultimately contributing to long-term safety and adaptability. This guidance is invaluable for developing a robust and organisation-wide risk management culture.

Sample Risk Attitude Statements

To illustrate how organisations can define their risk tolerance, here are some examples of risk attitude statements. These statements range from low to high-risk tolerance and demonstrate how you might approach security risks in different contexts.

Risk sharing with local partners

Both [INGO] and [L/NNGO] are committed to sharing risks equitably within the partnership. We will engage in regular joint risk assessments and reviews to monitor the risk environment and adjust our strategies accordingly. Each partner will contribute to developing and implementing risk mitigation plans, with clear roles and responsibilities outlined in our security and operational protocols.

Lower attitude

Our organisation operates with a low tolerance for security risks that could seriously harm staff, beneficiaries, or assets. We will avoid engaging in operations within areas experiencing active armed conflict or where the threat level is classified as extreme, unless comprehensive mitigation measures are in place to reduce the risk to an acceptable level. All activities in high-risk areas must receive senior management approval and be supported by a detailed and robust security plan. Our priority is to ensure the safety and security of our personnel and those we serve. We will take every precaution to avoid unnecessary exposure to danger.

Medium attitude

Our organisation has a cautious approach. We acknowledge that we operate in high-risk environments where external events or inadequate internal processes could lead to severe consequences. These might include death, injury, kidnapping, or trauma to staff members or others to whom we have a duty of care. We have implemented comprehensive policies, training, and monitoring processes to manage these risks. Given our presence in such environments, we recognise inherent security risks beyond our control. However, we are committed to minimising these risks through a cautious approach.

We will never compromise the security and safety of our staff and those under our care for financial reasons. We maintain a zero-tolerance policy towards non-compliance with our safety and security guidelines. Our security policies and procedures are designed to respond to the risk exposure in each context. While specific baseline security measures and training are mandatory for all international operations, our security protocols are tailored to each country. In higher-risk areas, stricter security procedures are enforced. As security risks escalate, our methods and protocols are adjusted accordingly, including evacuating personnel from the area.

Higher attitude

Our organisation operates in high-risk environments where serious consequences, including death, injury, or trauma to staff and those in our care, are possible. While we have traditionally maintained a cautious approach, the urgent need for humanitarian support requires us to accept a higher level of risk. To manage this, we have strengthened our policies, training, and monitoring processes to ensure they are robust and adaptable. We acknowledge that some security risks may be beyond our control. But we are committed to minimising these risks without compromising the delivery of essential aid. Despite our increased risk tolerance, our zero-tolerance policy for non-compliance with safety and security guidelines remains firm. We tailor security protocols to each context, with stricter measures in higher-risk areas. As risks escalate, our procedures will adjust accordingly, up to and including evacuation, while prioritising the continuation of critical humanitarian work.

Risk attitude is crucial for NGOs

A well-defined and documented risk attitude isn’t just for managing security risks. It’s also a critical asset that strengthens overall resilience and adaptability. By clearly defining acceptable risk levels, this approach guides decisions across all areas, including financial management, programme development, and compliance. It ensures that resources are used wisely and risks are managed consistently, balancing short-term needs with long-term goals. For INGOs working in complex, volatile environments, integrating a risk attitude into strategic planning is crucial for maintaining safety, meeting mission objectives, and protecting their reputation.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views or position of the author’s employers.

About the author

Alan Mordaunt is the Head of Global Security at Trócaire. He has over a decade’s experience in leadership and security risk management. This includes roles in the Irish Defence Forces and the United Nations. He has worked extensively in the Middle East and North Africa, most notably as part of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon.

Related:

Security Risk Management (SRM) Strategy and Policy Development: A Cross-Functional Guide

Having a robust security risk management (SRM) strategy and policy is critical for any NGO to achieve its mission. But for too many organisations, these don’t exist. Even when they are in place, strategies are often siloed within a single department. And policies may receive limited engagement from senior leaders.…

Partnerships and Security Risk Management: a joint action guide for local and international aid organisations

This guide aims to support L/NNGOs and INGOs in the aid sector to better manage and share responsibility for security risks in partnerships. It builds on findings from the GISF briefing paper, Security Management and Capacity Development: International agencies working with local partners, (2012) and GISF research paper, Partnerships and…

Sharing Risk for Equitable Partnerships: a case study from Nigeria

For years, Christian Blind Mission (CBM) and Sight Savers International (SSI) have supported local partners in Nigeria to implement development and humanitarian projects in the disability sector. Owing to growing insecurity in Nigeria, one of our local partners, HANDS, approached us to discuss funding for recruiting a Security Officer. CBM & SSI agreed to fund two Security and Safeguarding (S&SG) Officers for HANDS.