Insecurity Insight recently published a new handbook on security risk management in the health sector. Christina Wille explains why this is so urgently needed…

A new handbook to protect health workers

Healthcare needs to be protected from violence. But too often, health workers find themselves targeted or under attack. To address this, Insecurity Insight recently published a new handbook on security risk management, tailored specifically for the health sector.

Healthcare needs to be protected from violence. But too often, health workers find themselves targeted or under attack. To address this, Insecurity Insight recently published a new handbook on security risk management, tailored specifically for the health sector.

This handbook offers essential guidance for health programme managers and NGOs working with frontline healthcare partners. It also provides practical tools for improving security risk management in the health sector. For instance, by following this handbook, NGOs can strengthen partnership agreements and budgets to include security-related activities. This will allow them to foster safer, more resilient healthcare services.

Critically, the handbook also empowers local partners. It provides them with guidance tailored to their unique challenges. In this way, it serves as a foundational tool for localising security risk management – making healthcare delivery safer and more sustainable for all.

Why do we need specialised security for the health sector?

Insecurity Insight developed the handbook because healthcare faces unique risks during conflict. This requires a focused and adaptable approach to security risk management.

One unique aspect of healthcare is the fact that it must be delivered in person. Healthcare workers need to physically see and treat patients. This means they cannot operate remotely, even in the most dangerous contexts. With direct frontline engagement as a critical part of their roles, healthcare workers are naturally exposed to more risks.

Likewise, healthcare facilities must remain open and accessible to patients. Some humanitarian actors may take an approach of ‘bunkerisation’ during conflicts. This means they might cloister their work within walled compounds, protected by armed guards. But healthcare services cannot operate like a detention centre or enforce airport-level security protocols. Such overly restrictive security measures would give a negative impression that might push patients away. Overly stringent security might also create time delays and bottlenecks, potentially costing lives.

Finally, health workers may be targeted during conflicts. They may be perceived as supporting a particular side, based on who they are treating. Through the sheer nature of their work, healthcare providers also hold evidence for conflict-related crimes. For example, malnutrition rates recorded during medical consultations would be relevant in determining whether famine occurred in a particular area. These factors can lead authorities to arrest healthcare workers or armed actors to target health facilities.

Local workers bear the brunt of conflict violence

International agencies play a unique and vital role in supporting the health sector during conflicts. But most frontline healthcare and outreach services are delivered by local organisations, often outside the humanitarian umbrella. Voluntary and informal health services are also frequently relied on during periods of intense crisis. They fill critical gaps, reaching communities that might otherwise go without care.

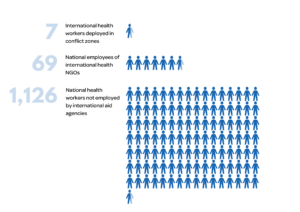

Insecurity Insight’s monitoring of violence against healthcare reveals a stark reality: local health workers bear the brunt of conflict violence. While it is widely known that national employees of international NGOs make up a significant proportion of aid worker fatalities, the data reveal an even more troubling trend among health workers who are not affiliated with international aid agencies.

Between 1 January 2023 and 31 October 2024, seven international health workers lost their lives. By comparison, 69 national staff employed by INGOs were killed. Most strikingly, however, 1,292 health workers killed in conflict were not directly employed by an international aid agency. This represents a staggering 87 per cent of the total.

Explaining the disparity in health worker fatalities

As the figure above shows, the gulf between aid worker fatalities among international and national providers is enormous. One factor driving this disparity seems to be the difference in the type of healthcare provided by international and national providers during conflicts.

International agencies typically implement qualified, dedicated security risk management appropriate for short-term specialised support deployments. This is because much of the work of international organisations focuses on:

- Sending specialised personnel or providing skills training in disaster- or conflict-affected areas.

- Supporting health facilities or programmes through donations, especially in prolonged conflicts.

- Organising logistics for health supplies, medical evacuations or referrals across conflict-affected areas.

In contrast, local partners typically provide frontline healthcare. This leaves them more exposed to risks. They require security measures that account for continuous interaction with communities and, in many cases, armed actors. They face unique challenges related to:

- Delivering essential care within health facilities, often close to combat areas and without job security.

- Conducting outreach campaigns in communities, including vaccination drives.

- Managing the daily operations of small and remote health posts.

- Living within, and often originating from, communities designated as the ‘enemy’.

Why local health organisations need tailored guidance

Recognising that security risks differ for INGOs and local health partners has important implications for security management. Expanding security risk management to local partners requires more than just sharing guidelines initially created by INGOs for their own operations. Effective ‘localised’ security risk management demands tools and guidance specifically designed to address the unique, continuous risks faced by local healthcare providers in conflict settings.

Aid agencies have long supplied local health facilities under attack with essential medicines and supplies. But they have seldom been able to offer comprehensive security support. Ensuring healthcare security in conflict zones requires a system-wide effort – with concrete measures to reduce, mitigate and prevent risks.

What is in the handbook?

Insecurity Insight developed the Handbook for Addressing the Risks of Violence against Healthcare in Insecure and Conflict-Affected Settings to guide health facility managers in low- and middle-income countries in managing security risks. The resource draws on best practices from international healthcare providers operating in conflict zones.

The handbook is available in Arabic, English, Spanish and French. It provides practical guidance for individuals or organisations on how to respond to violent incidents. It also covers how to deal with the aftermath of such events. And, it emphasises the need to balance protective measures with ensuring continued access to healthcare.

INGOs aiming to support security risk management within the localisation agenda can use the handbook as a tool for dialogue and joint work with local partners. This dialogue helps to identify priority areas where INGOs can develop tailored support to meet the specific needs of local partners.

The future of security risk management for the health sector

We recognise that the challenges facing health workers today are massive. Protracted conflict has become the norm, and we are seeing record-breaking aid worker fatalities.

Insecurity Insight’s new handbook cannot solve these challenges entirely. But it is a step in right direction. With this new guidance, we hope that international organisations can work to provide local partners with the security support they really need. That means support for communications, situation monitoring, contingency planning and much more – all of which you can find in the handbook.

Most critically, we hope the guidance will empower local organisations. By following the recommendations of the handbook, local organisations can build stronger security risk management systems – to protect those health workers who are most at risk.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views or position of GISF or the author’s employers.

About the author

Christina Wille is a founding member and Director of Insecurity Insight. Her work focuses on improving data collection on violence and its consequences for humanitarian aid. A German and Swiss national, Christina holds an MPhil in International Relations / European Studies from the University of Cambridge.

Related:

GISF Security Brief: 2024 mpox outbreak

Mpox is a zoonotic disease endemic in parts of Central and West Africa. But in recent years, the disease has spread widely, with more than 100,000 confirmed cases in over 120 countries. The situation is so severe that in August 2024, the World Health Organization declared the mpox outbreak a…

Protect Aid Workers: rapid support for aid workers in need

Protect Aid Workers is a new mechanism, supported by GISF, that provides financial assistance to humanitarian workers in need. David Annequin, who leads the initiative, explains what has been learned so far and how you can help.